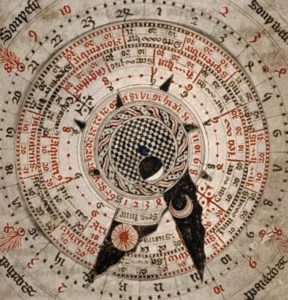

The volvelle, with its name coming from the Latin volvere, “to turn”, is a chart made of concentric paper circles held together with a tie or pin in the middle. In more recent decades, this construction might be a toy cipher wheel where lining up letters in a particular way corresponds to the key to crack a code, or it could be a playfully tactile part of an advertisement in a magazine, or it could be a way to present a medical chart such as a schedule for calculating fertility. The classical use of a volvelle was an astronomical chart and calendar, similar to the typically metal-wrought astrolabe. Dating back as far perhaps as the tenth and eleventh centuries, volvelles were included in manuscripts, perhaps pre-constructed or with instructions for assembly, with the circles corresponding to relative positions of the sun, moon, and stars. A volvelle could be manipulated to show where certain celestial bodies would be at any point in the year, and could even be held up against a night sky to determine what the time was, long before accurate timepieces could mechanically track the hours.

The astrolabe and the volvelle have been identified first in the Islamic world. In 1274, the volvelle was introduced to Europe by Ramón Llull, a writer and artist from Majorca, which is now Spain. He did not create his first volvelle to tell time by tracking the stars, though, in fact it was a divination tool using the nine names of God. Volvelles would be associated with mysticism, the occult, and divination for a long time, and were often used for fortune-telling. Llull did create a volvelle to tell time, later, in 1305, specifically because he believed that medicines had to be administered at exact times.

The astrolabe and the volvelle have been identified first in the Islamic world. In 1274, the volvelle was introduced to Europe by Ramón Llull, a writer and artist from Majorca, which is now Spain. He did not create his first volvelle to tell time by tracking the stars, though, in fact it was a divination tool using the nine names of God. Volvelles would be associated with mysticism, the occult, and divination for a long time, and were often used for fortune-telling. Llull did create a volvelle to tell time, later, in 1305, specifically because he believed that medicines had to be administered at exact times.

Volvelles have endured all the way to the present day, even if they are not always referred to by name; they can be found in various forms throughout the hand-press, machine-press, and digital era. Due to their ability to store information in an accessible format and their ability to calculate outputs from inputs (an “input” in this case would be turning the wheels to a particular position), they have been compared to computers and retrievable data storage devices like floppy discs.

If it is charming to know that inventions analogous to computers existed long before the digital era, it is surely also charming to see the possible print ancestor of the cursor or mouse. The most common cursor today is a stylized arrowhead, but when hovering over a link, one might notice the cursor turning into a tiny gloved hand with a pointing finger. This symbol might once be lumped in with the printer’s mark known as a manicule. Just like volvelles, these can be traced back to the the eleventh century, found in medieval manuscripts. They would point out sections of text, sometimes with amusingly elongated fingers or even distinctive artwork to suit the situation. Next to the wrist would usually be an additional bit of text annotating the passage. By later centuries this distinctive bit of embellishment would be formalized in a mark: ☞ .

This mark, also known as an index, a digit, a pointer, or an indicator, and would typically be seen in the margins where it first showed up in manuscripts. Since it was still a very personalized sort of mark, used to show a passage that a particular reader may have found interesting. Even though it had a typecast form, it could also still be inked in by hand. Fittingly, today’s computer cursors turn into manicules pointing at particular locations on a screen based on the individual user’s choice: whatever you want to investigate more of by following a link, there the finger will point. As a movable object in a virtual space, it becomes even more like the body part it is based on.