By Massiel Mota

November 19, 2017

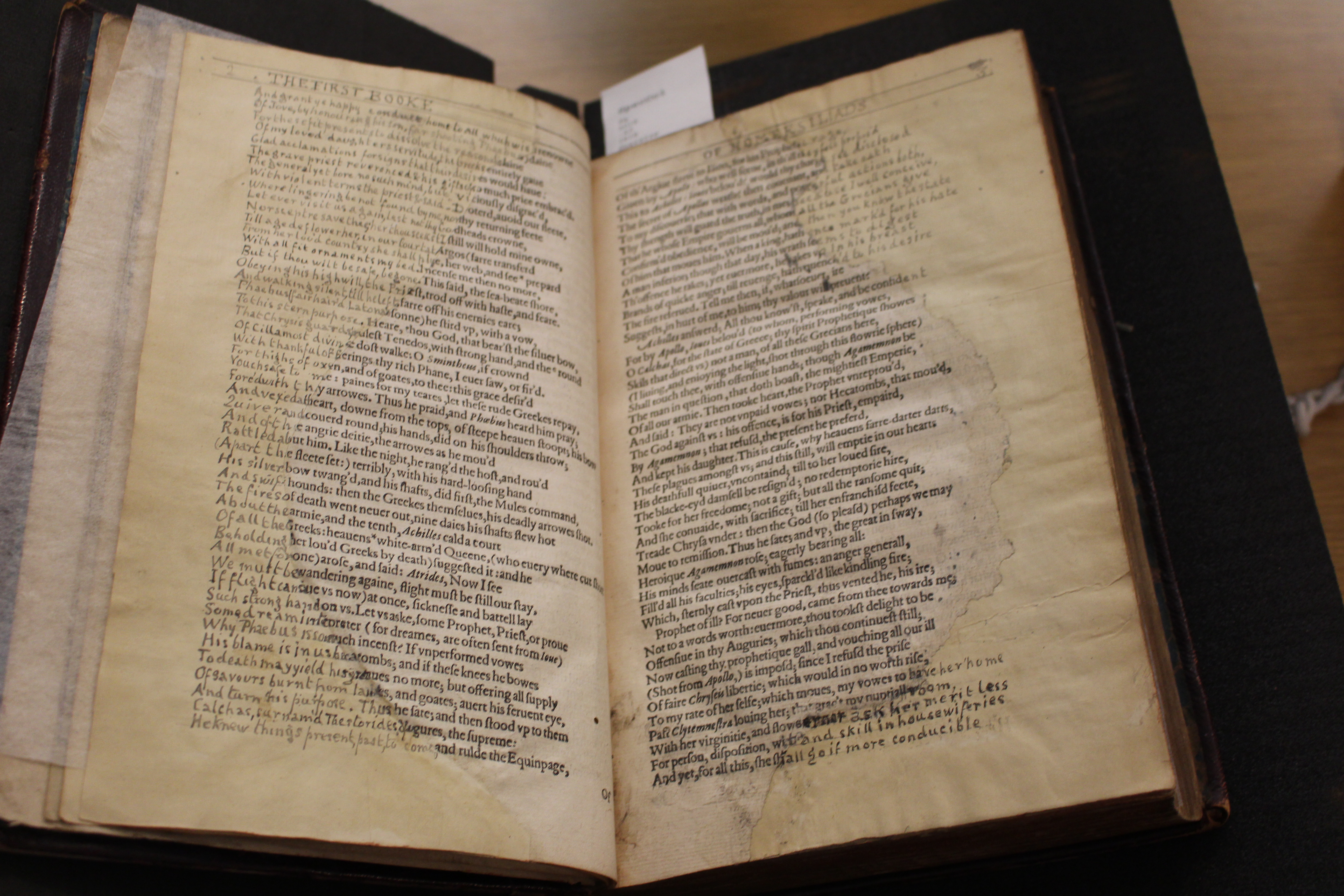

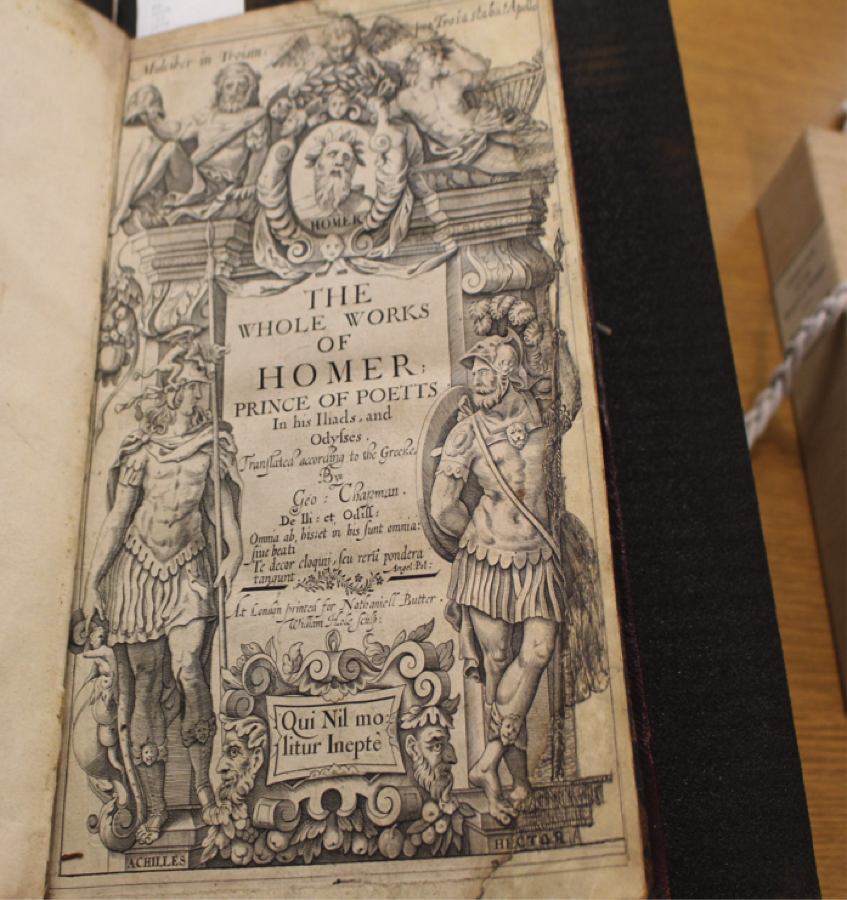

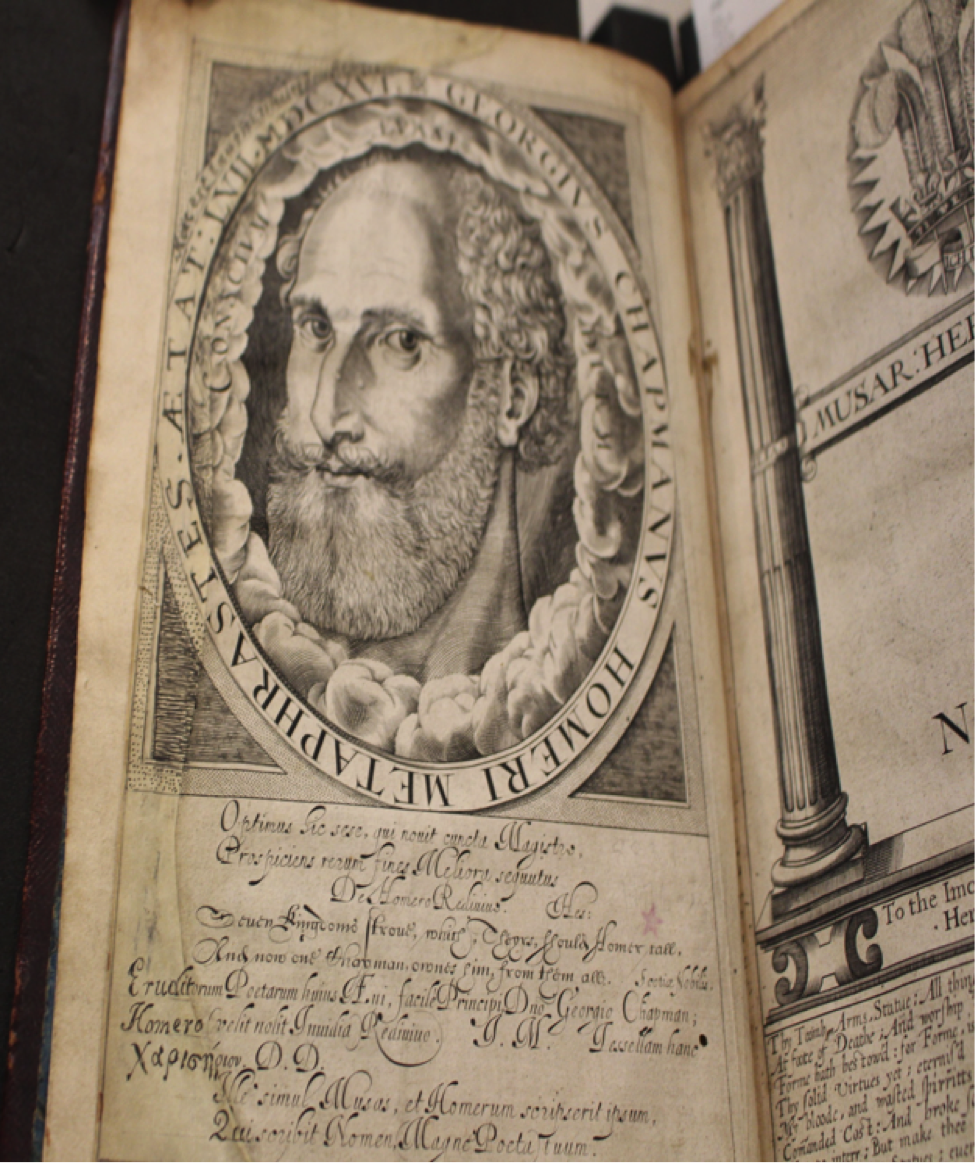

Much like Keats, my first encounter with Chapman was truly eye-opening. His etched face stared back in black lines on faded white paper from a worn and decrepit book. The edges of the pages had begun to be eaten by mice, yet someone took the care to rebuild the book, going so far as to mend the chewed pages and rewrite the missing words. Text that had disappeared with the rats was painstakingly recreated to the best of his or her abilities. The drawings and embellishments were matched almost to perfection (See figure 2). Clearly, someone not only cared about this book but cared so greatly as to bring it back from the brink of death, believing the words it contained to be of true value. This was my first encounter with George Chapman in his translation of The Whole Works of Homer, Prince of Poets, in his Iliads and Odysses. The text, printed in London for Nathaniell Butter in 1616, is now housed in the Fales Collection at NYU’s Bobst Library (See figure 1). Standing face to face with the remaining legacy of a man long dead, I wondered: Why was George Chapman so important? If he was so important so as to preserve his works from nature itself, why don’t I know more about him? If he was influential enough to merit a sonnet by Keats, what else has he done worthy of merit? In this vein I began my search in an attempt to bring George Chapman out from the shadows under which he has long lived.

Figure 1. The whole works of Homer, prince of poets, in his Iliads and Odysses. Translated by George Chapman. London: Printed for Nathaniell Butter, 1616. CUNY Fales Library. SpecCol PA4018 A3 1616 Oversize

George Chapman (Geo Chapman) is believed to have been born around 1559 in Hertfordshire, England in a town called Hitchin. He was the second son of Thomas Chapman and Joan Nodes. He was also a translator of great literary works; in particular, his translation of Homer long remained a standard English version aside from Alexander Pope’s. The first books of his translation of The Iliad appeared in 1598. It was completed in 1611, and his version of The Odyssey appeared in 1616. His aim with these translations was to “establish a national literature powerful enough to rival the Latin and the Greek. In his poetic canon, including his Homeric translations, Chapman constantly aims to convert Greek and Latin poetry (classical as well as contemporary) to native English, and claims as well an attempt to surpass his predecessors” (Snare).

In fact, it is this translation of Homer that inspires the famous sonnet, “by John Keats. Keats writes:

But of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet could I never judge whawt men could mean

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold, (ll. 5-8).

Upon Keats’ entering of Homer’s domain, he immediately becomes indebted to Chapman for without Chapman, Keats would not know of Homer’s Greek classic texts. Chapman in a way becomes the catalyst that plunges Keats headfirst into a realm completely unknown and forbidden to him. This is extremely interesting considering that while Chapman attended Oxford, he received no degree. Already, this preconceived notion of a stereotypical and extremely academic man producing such great literary translations has been broken. Although Chapman must have been greatly educated in the Greek and Latin language to produce these translations, it seems not to have been through formal academic institutions that he attained this knowledge. Coincidentally, Keats finds himself in similar conditions to Chapman when inspiration strikes him to write in his honor. Susan Wolfson writes of Keats, “Here he was in the summer of 1816, without parents but with good friends, counselors, and sponsors; without a university education and connections, but qualified for a career as a general medical practitioner” (20). It seems that both these men of literary greatness decided to forgo the standard university education but still managed to go beyond the academic world to cement themselves in an everlasting paradise of classic literature. Beyond his works translating classic texts, Chapman was also a poet and dramatist. His first work was The Shadow of Night . . . Two Poeticall Hymnes (1593), followed in 1595 by Ovids Banquet of Sence (George Chapman).

Figure 2. The whole works of Homer, prince of poets, in his Iliads and Odysses. Translated by George Chapman. London: Printed for Nathaniell Butter, 1616. Fales Collection, NYU Bobst Library. SpecCol PA4018 A3 1616 Oversize

Keats’ debt to Chapman is something that has not gone unnoticed, though it has been unappreciated. Fellow poet, Keats biographer and collector Amy Lowell once suggested: “If anyone would have a grateful task, let him track Keats’s indebtedness to Chapman’s Homer. There is an ample field and practically unexplored” (Landrum). Taken to task, Grace Warren Landrum writes, “I have by no means exhausted the study of Chapman’s rimes, but I have compared practically every irregularity of Keats (except in sportive verse) with hundreds of corresponding defects in the Homeric translations.” It seems Keats’ debt to Chapman as his muse expands far beyond his tribute with “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer”. However, in writing about Chapman’s translation of Homer, it is equally as important to discuss Alexander Pope. Alexander Pope also translated Homer’s works and, in fact, it was his version of translations that were the most popular of the time. Landrum writes, “[Of Chapman’s translations] it is easy to assume that defects of Keats’ household speech made acceptable to his ear harsh rimes which cultivated taste of his day rejected.” Even biographer Nicholas Roe concurs with Landrum in his book John Keats: A New Life, by writing, “When Keats celebrated George Chapman’s English rendering of Homer, even a well-intentioned critic noted that his recourse to a translation signaled insufficient ‘intellectual acquirement’” (38). Given that Keats was not university educated and did not come from vast wealth, it can be easy to see why perhaps Keats identified with Chapman’s “blue-collar” version best.

Wolfson goes further to compare how Pope and Chapman’s translations differ in sound. While Pope had a halting style of writing, Chapman’s verses gallop fluidly. She writes, “Compare Pope’s ‘From mouth and nose the briny torrent ran’ to Chapman’s “The sea had soak’d his heart through” (21). This fluid galloping style of writing is not lost on Keats who adopts the method of Chapman. In his sonnet, “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer”, we see the same nuances presented by Chapman originally. Line 2 reads, “And many goodly states and Kingdoms seen.” The same melodious effect is felt by the reader when reading both Chapman and Keats. Another example of Keats’ emulation of the galloping style in his sonnet “On the Grasshopper and Cricket”. Lines 1-4 creating the first quatrain can be read in one fluid motion as:

The poetry of earth is never dead:

When all the birds are faint with the hot sun,

And hide in cooling trees, a voice will run

From hedge to hedge about the new-mown mead;

The commonality between Keats and Chapman’s verses can be considered as more than simply stylistic coincidences. Through his good friend Charles Cowden Clarke, Keats had access to both Pope’s version of translations as well as Chapman’s version (Wolfson 20). However, through Keats’ subsequent writing, we are able to see the lasting effect that Chapman had on Keats which Pope did not.

It is perhaps ironic that my search for George Chapman brought me right around to John Keats again. These two men, separated by over a hundred years, were more similar than they realized. Both sought to seek the written word as an art form without the encumbrance of academic institutions. Both of these men were perhaps unappreciated in their times though greatly admired today. Through his translations, Chapman molded the verses of Keats, writing that we so admire today. Upon reflecting on my time standing in the center of a library’s special collections room on an ordinary Friday afternoon, staring at a table holding the tattered remains of Chapman’s work, I now see how the two men reached through the centuries to memorialize each other in verse. I was able to visualize the admiration that Keats might have felt for Chapman when he read the words in his book, much like the book of Chapman’s translations lain before me. Through the immortality of words, transcendent of time and space, Chapman’s book of translations The Whole Works of Homer; Prince of Poetts in his Iliads, and Odylses (Attachment 1) is the embodiment of Keats and Chapman’s brotherhood in literature.

Works Cited

“George Chapman.” Britannica Academic, Encyclopedia Britannica, 1 Nov. 2017. academic.eb.com.lehman.ezproxy.cuny.edu/levels/collegiate/article/George- Chapman/22482. Accessed 18 Dec. 2017.

Landrum, Grace Warren. “More Concerning Chapman’s Homer and Keats.” PMLA, vol. 42, no. 4, 1927, pp. 986–1009. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/457548.

Roe, Nicholas. John Keats: A New Life. Yale University Press. 2013.

Snare, Gerald. “George Chapman.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/george-chapman. Tulane University.

Wolfson, Susan J. Reading John Keats. Cambridge University Press. 2015.