by Jerlisa Ware

Before attending this Senior Seminar class, I came in with minimal knowledge about the great John Keats. The only Keats work I was familiar with was “Ode on a Grecian Urn” from a few of my college classes. But, we never went in depth as to who he was as an individual and what inspired him to become a writer in the first place. To be honest, I didn’t think that I would find someone’s life so interesting, especially since teachers always gave students the basic facts about the authors’ works we were learning that week. The library trips were an added bonus to my learning experience. The library visit to New York University’s Fales Collection is what gave me the spark for the topic of my final paper.

While visiting the NYU Fales Collection, the curator delved into the Gothic era of literature. She explained that Gothic works were seen as everything that wasn’t considered the “proper literature.” This genre was starting to cause a stir in the literary world, particularly because it came during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century where things were quickly changing. Some of these included: the French Revolution where identity and social class were drastically changed in favor of everyone who wasn’t seen as royalty; Challenging set religious thoughts; the rise of the Industrial Revolution; The spread of revolutionary ideas of the Enlightenment Era. The Gothic novel was a perfect piece in this “era puzzle” and it was a time where these authors were able to express their out of the box views.

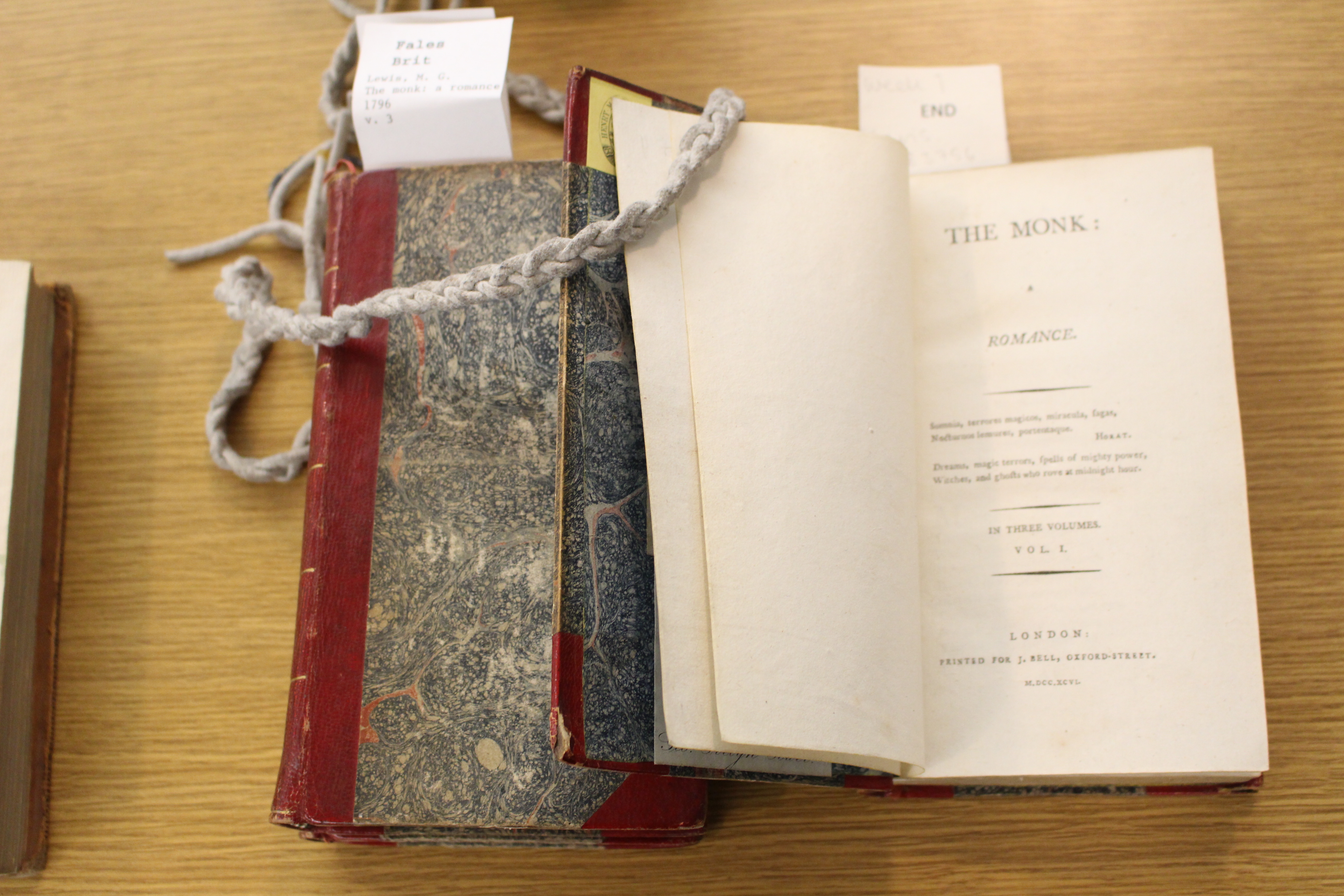

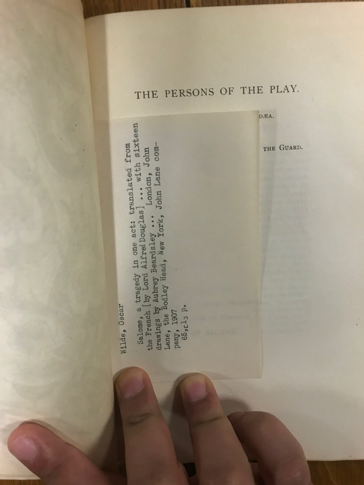

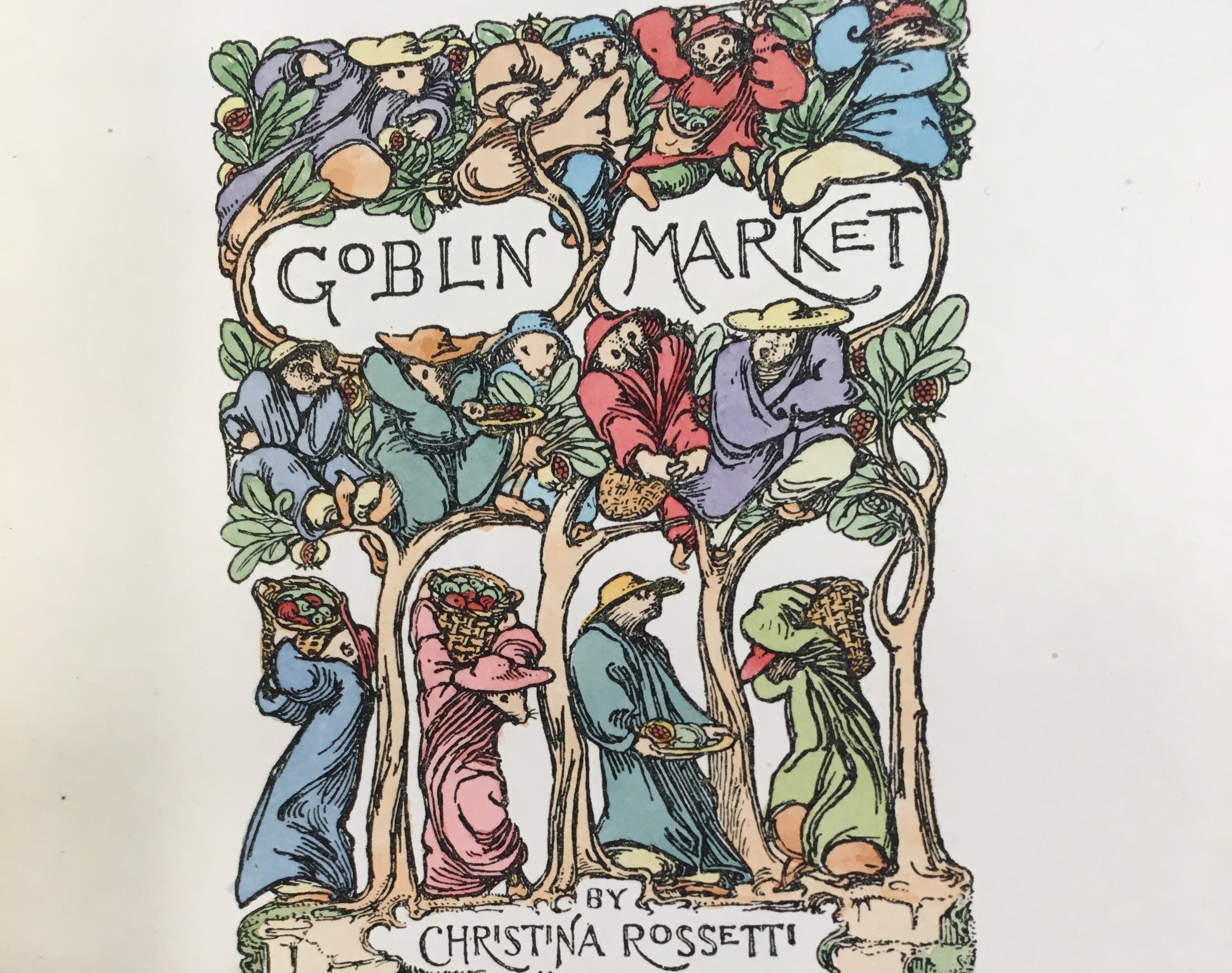

After the NYU Fales Collection tour, I was able to briefly talk to curator Charlotte Priddle about what texts and authors played a part in the Gothic literature era. She showed me The Monk by Matthew Gregory Lewis which is considered the face of this genre. Then she started to show me works by women authors that she considered to be great writers of that time. These works and writers included: Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho; Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice; Ann Radcliffe’s The Italian; Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. This immediately caught my interest because I never knew there were so many woman authors of that time besides the popular ones we learned about. Second, it made me think how amazing it was that women who were only looked at as wives and nothing else, were doing all the things that society dreaded during that time. This library trip made me go home and research these women to find out how their writing made some big noise in the literary world. One article I found on Romantic Circles explained the depths of Jane Austen’s work. Eric Eisner, a professor at George Mason University describes the Gothic Novel and its “prominence in the literary landscape in which Austen habits of reading and writing took shape” (Mason 1). Eric Eisner states, “I hoped students would see that both Austen’s fiction and Gothic novels of the 1780s and 90s respond to a social world in transformation, participating in the cultural debates swirling around key institutions—marriage, the family, patriarchal authority, property transmission.” Jane Austen put to the forefront, her opinions and the reality of society’s values and the problematic expectations people of her era forced upon women. She was even known to protest against the story lines that were found in Romantic and Gothic literature. We see this in her novel, Northanger Abbey which was a parody of Gothic literature and Romantic ideals. Jane Austen was definitely a writer in her own lane and she had a unique writing style because of it. According to Richard Turley, a creative writing professor at Aberystwyth University, “Her novels are attuned to all those petty ambitions, desires and jealousies we like to think we keep hidden from our peers. We take vicarious pleasure in seeing hypocrites exposed and social climbers ridiculed” (Marggraf Turley 1). Again, we know that Jane Austen liked going against what’s deemed proper. Not only is she an outspoken woman, but she is also poking fun at a patriarchal society. As I continued to dig up more information about woman authors in the Gothic era, Ann Radcliffe was repeatedly brought up as one of the founders of Gothic fiction. She had a way of combining horror and terror in a way that made some people uncomfortable while others found themselves enjoying it. Dale Townshend, a Professor of Gothic Literature in the Centre for Gothic Studies at Manchester Metropolitan University states:

Even as critics and reviewers in the 1790s castigated Gothic fiction as the ‘trash of the circulating libraries’ – that is, as a cheap and tawdry form of popular entertainment that, in its formulaic and highly repetitive nature, fell foul of the emphasis that emergent Romantic aesthetics placed upon the category of ‘original genius’ – Radcliffe was consistently singled out an exception, as the one writer who was deservedly exempt from the general condemnation of Gothic writing in Romantic-period culture. (Townshend 1).

Just as Jane Austen and many other woman writers of that time, Ann Radcliffe was a women with a voice. She didn’t let the naysayers disrupt her writing journey. As a result, she became one of the highest paid professional writers of her era. She was also the most rivaled, copied and plagiarized author of her time period. Not too bad for someone who wrote in a genre that was looked upon as comical against the “proper literature” written by other people.

All of the information I researched, made me think about how John Keats was also a person who wandered outside of the literary box. He was very outspoken about the limits people put on any type of writing.

During the library visits, we were able to actually see the letters that Keats sent to the people who were close to him. It was amazing to see the handwriting of a famous author. Letter writing was a lot more personal and you could see the thought that went into it. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to attend the Princeton University Library trip, but I was able to pull up the letters I was looking for on the Keats Letter Project website. John Keats’ letter to his brothers George and Tom Keats (provided by Princeton University Library) talked about the concept of negative capability. This is when a “man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason” (Keats 78). Keats believed that in order to make true poetry, a writer had to take out their doubts and questions that would block them from truly digging into their imagination. In many of his letters, he mentioned that men do not hold any sense of individuality and a determined character. To be able to have negative capability, means to have an open imagination and being able to accept the unknown. According to Susan Wolfson, “The ‘new Romance’ that Keats projected to Reynolds would ruffle the market on two fronts, and with gendered force: exposing the delusions of ‘old Romance’ and casting modern meta-Romance, its devices demystified, its spells spelled out …” (Wolfson 50). We see this put into action in Keats’ work Isabella; or, The Pot of Basil. He classifies this writing as the “anti-Romance.”

Being able to write outside the literary box also made me think of John Keats’ Incipit altera Sonneta. In this sonnet, Keats is criticizing the repetitive nature of how to write poetry. Keats states, “I have been endeavoring to discover a better Sonnet Stanza than we already have. The legitimate does not suit the language over-we from the pouncing rhymes-the other kind appears too elegiac-and the couplet at the end of it has seldom a pleasing effect” (Keats 254). He believed that the process and ending result of writing poetry is all the same with no lasting effect. Keats admitted that he didn’t have the perfect formula in writing the perfect sonnet, but he did think that he could do a lot better than the writers that were coming up with them. He then goes on to say, “So, if we may not let the muse be free/She will be bound with Garlands of her own” (Keats 255). Here, Keats is explaining the dangers of being constrained and restricted in the repetitive methods of writing poetry. If a writer doesn’t allow themselves to think outside of the literary box, they become prisoners of their actions.

As a whole, the library trips for this senior seminar class opened up my thoughts on what literature consists of. Even though this was a class that was centered on the great John Keats, I was able to dig deeper into the authors that also saw literature in the same light as him.

Works Cited

Eisner, Eric. “Jane Austen and the Gothic.” Romantic Circles: A refereed scholarly Website devoted to the study of Romantic-period literature and culture, 2015, https://www.rc.umd.edu/pedagogies/commons/austen/pedagogies.commons.2015.eisner.html. Accessed 17 December 2017.

Mudallal, James Al. “Why Pride and Prejudice is as relevant today as it ever was.” Wales Online, 1 April 2013, http://www.walesonline.co.uk/lifestyle/showbiz/pride-prejudice-relevant-today-ever-2498188. Accessed 17 December 2017.

Townshend, Dale. “An introduction to Ann Radcliffe.” The British Library, https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/an-introduction-to-ann-radcliffe. Accessed 17, December 2017.

Wolfson, Susan J. Reading John Keats. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Wolfson, Susan J. A Longman Cultural Edition John Keats. Pearson Longman, 2007.

One thought on “Women Gothic Authors: Writers Outside the Literary Box”

This is a good informative article with a nice style.