The Grolier CIub housed Lisa Unger Baskin’s Five Hundred Years of Women’s Work, that showcased the labor of several women from different century periods. The 49-year-old bibliophile, activist, and collector assembled a variety of documentations of women at work. Baskin’s first collection arrived at Rubenstein Library in Durham, North Carolina in April 2015, and since then has been attracting rare book lovers and scholars.

Among the 17th century section is a first edition book of poems of Phillis Wheatley, the pioneer of African American literature who inspired fellow African slaves through her work and contributed to their acknowledgement as equally intellectual and capable, which influenced the abolition of slavery and civil rights in America. Though highly cracked, the ink quality is neatly preserved, and the stitched pages which seem to follow the octavo page-folding format, still hold together. To the left is seen an engraving of Wheatley seating with a pensive pose holding a quill pen, and dressed with a servant uniform. Around her portrait, a statement of herself reads, “Phillis Wheatley, Negro servant to Mr. John Wheatley of Boston.” This edition was published in 1767 When she was only a 14-year-old, and is considered as symbol of women empowerment as well as gender and race equality.

Among the 17th century section is a first edition book of poems of Phillis Wheatley, the pioneer of African American literature who inspired fellow African slaves through her work and contributed to their acknowledgement as equally intellectual and capable, which influenced the abolition of slavery and civil rights in America. Though highly cracked, the ink quality is neatly preserved, and the stitched pages which seem to follow the octavo page-folding format, still hold together. To the left is seen an engraving of Wheatley seating with a pensive pose holding a quill pen, and dressed with a servant uniform. Around her portrait, a statement of herself reads, “Phillis Wheatley, Negro servant to Mr. John Wheatley of Boston.” This edition was published in 1767 When she was only a 14-year-old, and is considered as symbol of women empowerment as well as gender and race equality.

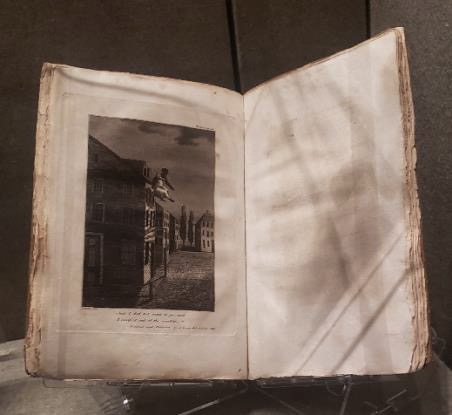

The collection also displayed an 1817 publication of physician Jesse Torrey, A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery, in the United States, inspired by the suicide attempt of Ann Williams, a woman sold with her children to slavery in November of 1815. The painting in this page of Torrey’s publication vividly shows Williams jumping out the third-story window. Looking closely at the engraving, the desperate  woman can be seen in the air wearing a white dress, not so far from the floor. Williams did not die, but her back and arm were irremediably broken. Torrey was visiting when she came across Williams’s sad scenario, which inspired him to unite the account with other narratives as a way to raise awareness. To see this in person is of course not as vivid physically materialized, but feels definitely as it would if saddening picture alone; it transports any viewer to slavery periods. The painting justice; can easily denote advocacy and desire to and while demand reading that Williams was able to freedom and her children obtain her feels alleviating to a certain extent, her case makes the viewer wonder the probably did not enjoy the same fate. The book’s physical condition is fairly stable though with torn edges similar to those in Wheatley’s edition, also using black and white tones. The folding format seems to be quarto style, and next to Williams’ engraving lies an empty page apparently marked with ink residues. A very simple book full with a complex story.

woman can be seen in the air wearing a white dress, not so far from the floor. Williams did not die, but her back and arm were irremediably broken. Torrey was visiting when she came across Williams’s sad scenario, which inspired him to unite the account with other narratives as a way to raise awareness. To see this in person is of course not as vivid physically materialized, but feels definitely as it would if saddening picture alone; it transports any viewer to slavery periods. The painting justice; can easily denote advocacy and desire to and while demand reading that Williams was able to freedom and her children obtain her feels alleviating to a certain extent, her case makes the viewer wonder the probably did not enjoy the same fate. The book’s physical condition is fairly stable though with torn edges similar to those in Wheatley’s edition, also using black and white tones. The folding format seems to be quarto style, and next to Williams’ engraving lies an empty page apparently marked with ink residues. A very simple book full with a complex story.

Works Cited

- Torres, Jesse. A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery, in the United States. Philadelphia, 1817.

- Contribution to History and Literature, www.phillis-wheatley.org/influence/. Michals, Debra. “Phillis Wheatley.” National Women’s History Museum, www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/phillis-wheatley.

- Schuessler, Jennifer. “The Overlooked History of Women at Work.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 16 Jan. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/01/16/arts/design/womens-work-grolier-club.html.