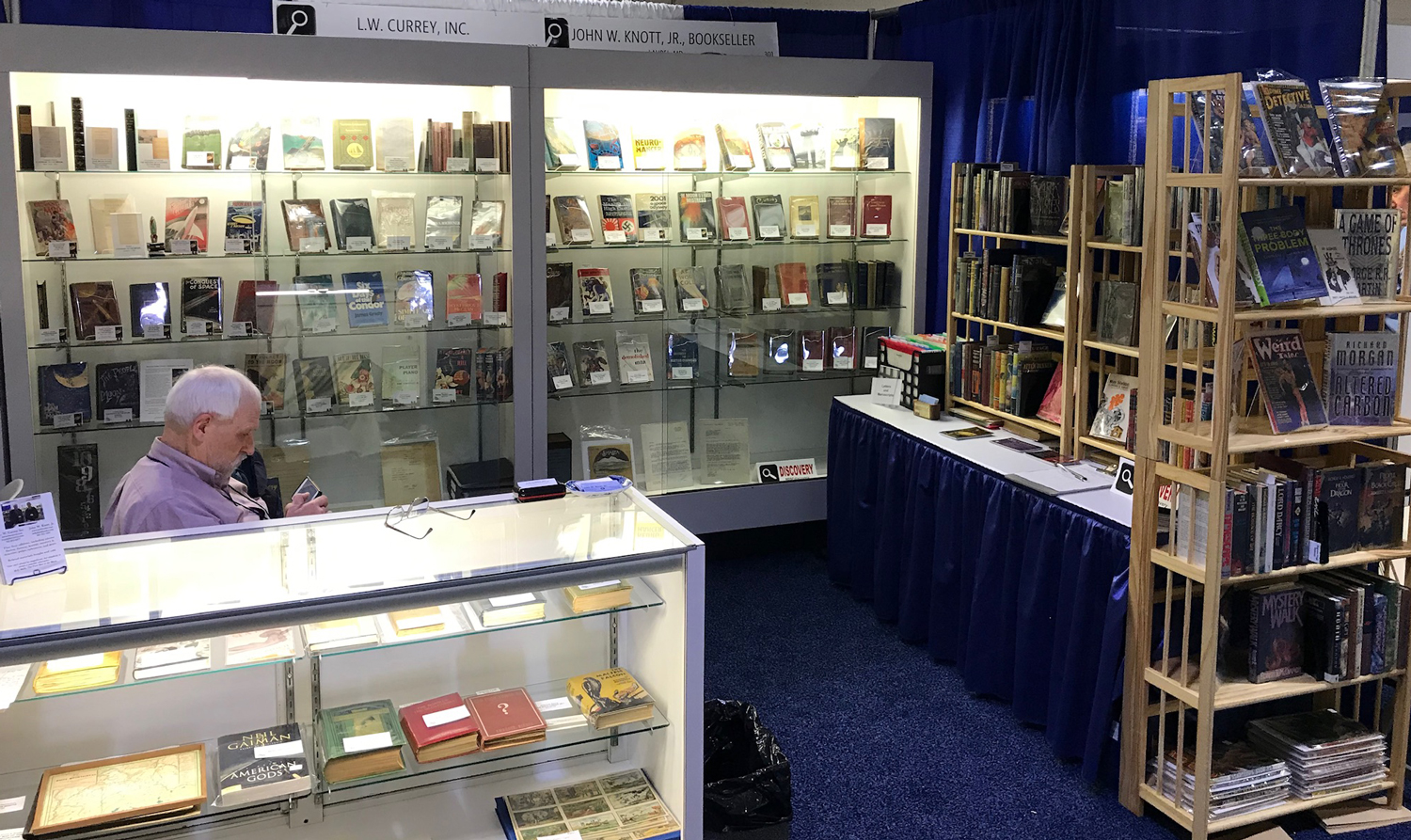

How do we discern a book’s value? Sellers and buyers in the antiquarian book trade judge market value through the rarity, scarcity, condition, and history of the items which are circulated. The 58th International Antiquarian Book Fair demonstrated that worth is not only found in the content, but in the beauty of the object as well. The fair had numerous collections of rare books, maps, manuscripts, and ephemera. Many vendors warned me to not look for what would havethe best resale value, but to seriously consider what was popular in terms of what was both best-selling and impactful in terms of cultural influence. Upon asking for advice on becoming a collector, I was immediately told: “Don’t think of how much you can sell it for; make sure that you start collecting what you’re interested in!”

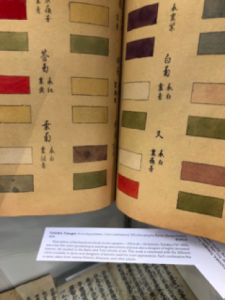

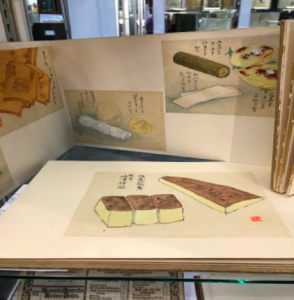

I mostly found myself gravitating towards booths which focused on children’s books and fairy tales, but ultimately spent the most time looking at whatever Asian works I could find. I spoke with Megumi Kaneko Hill and Timothy Yoshiro “Yoshi” from Johnathan A. Hill’s antiquarian book company, who informed me that they had only recently started dealing with Japanese work and literature. It was Yoshi who discovered Japanese illustrated acupuncture and medicine books at another antiquarian book fair and helped kickstart their specialization in antiquarian Japanese and Chinese illustrated books, manuscripts, and scrolls. When they first began collecting, Megumi and Yoshi built up their reference books, solemnly stating “Booksellers need these; they can’t do antiquarian work without them.”

Megumi shared that she found immense excitement in the items to be catalogued and oftentimes needed to rely on a handbook which organized dates and eras to supply information on which time period each item came from. She and Yoshi also spoke to me on the antiquarian book scene in Japan and its distinct uniqueness from American rare book trading. Guilds happened to play a large role in Japanese antiquarian book fair trading. Unlike auctions held in the United States where anyone could bid and buy, participants in Japanese auctions needed to be in a guild. Those outside of the guild needed to ask a guild member to purchase for them. The first bookseller’s guild was formed in Kyoto in the late seventeenth century and was officially recognized by the authorities in 1716. Similar guilds later followed in Osaka (1723), Edo (1725), and Nagoya (1798). Trade guilds were only accepted by the government for the sake of limiting disputes over copyright.

I thought back to the smattering of Japanese works amongst Western manuscripts and literature I saw while walking around the Fair and asked Megumi her opinion on the demand for Japanese art. She replied that the Japanese and Western art world have been heavily influenced by each other. Many artists in Europe were influenced by the techniques and lines which were usually not taught in the schools of art. Aubrey Beardsley, who I am currently researching on, was heavily influenced by the ukiyo-e style, the genre of Japanese art which flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. While there are cultural inspirations such as kabuki present which may be unknown to an outsider, Megumi made it clear that in the antiquarian book trade, knowledge of Japanese was not necessary, smiling as she told me “collectors, sellers, and buyers simply just need a mutual sense of love and respect for these books to speak with each other.”