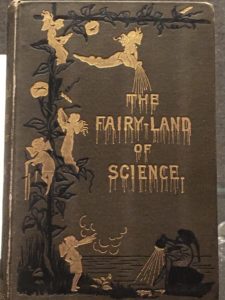

With its whimsical and inviting cover illustrations, The Fairy-Land of Science, found at the Grolier Club’s exhibition of the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection called Five Hundred Years of Women’s Work , reaches out to its intended audience of children by promising the kind of magic they’d find in a Brothers Grimm collection. Fairies play along a vine and trellis, and a strange creature sits pensively in the bottom corner — a little angelic being pensively seated upon a rock with a lamp for a head. The author of this book, Arabella Buckley, was connected to many of the famous men of science in the late 1800s, including Alfred Wallace, Charles Darwin, and Thomas Huxley, starting with the geologist Charles Lyell in 1864 who she worked for as a secretary. Buckley became a popular science writer after Lyell passed away in 1875. The Fairy-Land of Science is one of the books she wrote for younger audiences, and it promises that science will be as enthralling as fairy tales.

, reaches out to its intended audience of children by promising the kind of magic they’d find in a Brothers Grimm collection. Fairies play along a vine and trellis, and a strange creature sits pensively in the bottom corner — a little angelic being pensively seated upon a rock with a lamp for a head. The author of this book, Arabella Buckley, was connected to many of the famous men of science in the late 1800s, including Alfred Wallace, Charles Darwin, and Thomas Huxley, starting with the geologist Charles Lyell in 1864 who she worked for as a secretary. Buckley became a popular science writer after Lyell passed away in 1875. The Fairy-Land of Science is one of the books she wrote for younger audiences, and it promises that science will be as enthralling as fairy tales.

In the book’s introduction, Buckley writes, “There are forces around us, and among us, which I shall ask you to allow me to call fairies, and these are ten thousand times more wonderful, more magical, and more beautiful in their work, than those of the old fairy tales.” Her writing is as full of pathos and poetry as a fairy-tale writer’s, and so it is important that the book’s cover reflects this authorial style which is her strength. Most of the fairies could belong in any fairy tale book, but the way they interact with the title, with one dousing it in water and another blowing up at it, perhaps to chill it, takes on more meaning when you understand how Buckley wants to portray forces of nature as fey-like, and that these fairies must specifically represent the forces of rain and wind. But without that context, the lamp-headed fairy is the only indication besides the title that this book will not be about typical fairy tales, and it is depicted with black outlines rather than the gold of the others, clearly to make its glowing light more recognizable, but this also has the effect of making it seem less magical than the rest. I saw this fairy representing technology, and the part of it that is a natural force is embossed in gold like the other fairies but the part that would be static without those forces, the man-made device, is dark.

Buckley seems to understand not only that science can be made appealing by speaking to a childlike desire for wonder, but that books in particular promise those wonders, and when a child reads a book they may feel they are stepping into a secret bound and printed just for their eyes. Since I grew up reading popular science books, I have a lot of nostalgia for them. I also recognize that the narratives popular science writers use to capture their readers’ attention widely impact people’s understanding of science, for good and for ill. The history of popular science writing must be important to sociological studies of science. And of course, since women historically have been denied equal access to positions of authority in science, but have also tended to have more traction in careers involving children, it is admirable that Arabella Buckley made a career writing about science specifically to have a formative impact on younger generations. When it comes to the making of a scientific mind, some of the most important influences in one’s life can be those books about science read in childhood.