While Leah Price is one of The Book’s big defenders and believes in it being revered, she also acknowledges the popularity of modern technology and the fact that it does not seem to be going anywhere anytime soon. In chapter two of What We Talk About When We Talk About Books, she brings up the point that books as objects were not always these sacred, timeless pieces of art that we often make them out to be in our romanticizations of the past. Papal indulgences were made more frequently than books were during Gutenberg’s time, were produced in higher quantities, and were not regarded highly in the slightest. However, more of these old sheets of paper survive in libraries today than Gutenberg Bibles. Price points out that those today who criticize Twitter, text messages, and blog posts for spoiling our palettes for great literature are forgetting that printers like Gutenberg and Ben Franklin were making “bite-sized, ephemeral, and profit driven” pieces of writing long before the existence of social media (Price 58).

during Gutenberg’s time, were produced in higher quantities, and were not regarded highly in the slightest. However, more of these old sheets of paper survive in libraries today than Gutenberg Bibles. Price points out that those today who criticize Twitter, text messages, and blog posts for spoiling our palettes for great literature are forgetting that printers like Gutenberg and Ben Franklin were making “bite-sized, ephemeral, and profit driven” pieces of writing long before the existence of social media (Price 58).

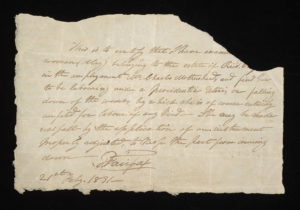

Throughout these chapters, Price discusses the ever-present fear of books becoming obsolete and their resilience to withstand the test of time. In this History of Bibliography course we have discussed the preservation of books as material objects, but we have also discussed the preservation of miscellaneous pieces of text and writing as their own unique windows into the past. For example, on our field trip to the Grolier Club we saw a board covered in what we now call business cards from hundreds of years ago as well as a note from a doctor who treated a slave woman (see photo)—these items would not have been considered “literature” at the time they were created, nor would have even been considered important documents. Their preservation over time allows for us to see what was important to people during the time they were created, but it also shows us that literature—no matter how bite-sized—will always be a part of our lives.