The Mark Samuels Lasner Collection at the University of Delaware held an unpublished letter and biographical entry by English essayist and aesthete Walter Pater (1839-1894) and bore the unofficial title of “My dear Madam,” Reference Code:105880. It was sold to the Lasner Collection for USD $600. Below are the original photos taken of the pieces, followed by transcriptions and analyses.

ARTICLE I

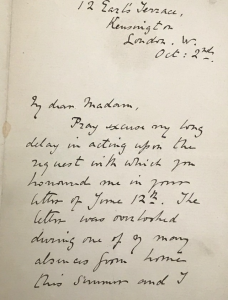

12 Earl’s Terrace,

Kensington

London. W.

Oct : 2nd

My dear Madam,

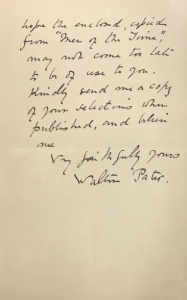

Pray excuse my long delay in acting upon the request with which you honored me in your letter of June 12th. The letter was overlooked during one of my many absences from home this summer and I hope the enclosed, copied from “Men of the Jurie,” may not come too late to be of use to you. Kindly send me a copy of your selections when published, and believe me.

Very faithfully yours

Walter Pater.

ARTICLE I: ANALYSIS

In this nondescript letter written roughly in 1891, Walter Pater is thanking a currently unnamed woman for honoring him in her speech of June 12th, circa 1890. Pater’s biography was to be added to the woman’s collection (likely an early anthology) of Aesthetic writers and classicists, his biography being copied from an existing text titled “Men of the Jurie.” This text as well has also gone unidentified, I conclude because of a name change toward the end of publication and production, or that it did not have many sales during the run of its publication. His summer of 1890, purportedly had been spent through scrutiny in connection to his office at Brasenose, Oxford as well as treatment for his health, as he passed away three years after this letter was written.

Contextually, he faced harsh criticism for his Renaissance book in which he endorsed amorality, hedonism, Platonism and male beauty, bonding and physical sensuality between one another, and expulsion of religion in all of this. Given his spiritual successor Oscar Wilde’s conviction for his homosexuality, and Pater’s lack of romance toward women (openly at least), he likely spent his last years under criticism from names like George Eliot and influential tutor Benjamin Jowett. Letters emerged in the 1980’s regarding his homosexuality through letters identifying a romance between Pater and William Money Hardinge, who had garnered unfavorable attention because of his outspoken sexuality expression, and Pater’s continuous writings on male bonding propagated his academic downturn. I originally presumed his “My dear Madam” letter to remark a woman of romantic attachment, but this was proven false through analysis of his connections to other prominent names of the 1890’s. Instead, this was an act of polite diction per Victorian England standards.

The letter was curiously in fine condition, the paper being of a sturdier and rougher material than modern papers granted of its imprinting and composition originating in the 17th and 18th centuries). The letter, being of A5 measurements (5.8″ x 8″) was folded into four even spaces, implying that it was carried rather than filed in a folder or a desk, while having rough dimensions and texture. Its scent did not have any noticeable fragrance. Observing the letter in person assisted in identifying the rushed cursive toward the end of the letter and several underlines under any notation of tenths (5th) and seemed that Pater had been in a hurry.

The following text is paired with Article I above; it is the biography Pater directed to the unnamed woman to be printed in her book, presumably a collection of aesthete authors.

ARTICLE II

W.P. was born in London, on Sunday, Aug. 4, The Feast of S. Dominic, 1839, and educated at The King’s School Canterbury; he entered the University of Oxford, at Queen’s College, in 1858; took B.A. degree (2nd class in Classics) in 1862; was elected to an open Fellowship at Brasenose, in which college he has since held various offices, and took the degree of M.A. in 1865. W.P. has made many visits to Italy, France, and Germany. His first contribution to literature was an essay on the Writings of Coleridge in the Westminster Review, Jan: 1866. Jan 17 1873 “The Renaissance” (Macmillan) a series of Studies in Art and Poetry: 5th Thousand, 1890. In 1885 appeared “Marius the Epicurean; his Sensations and Ideas,” in 2 vols: 4th Thousand, 1890: -. Jan 1887, “Imaginary Portraits”: 3rd Thousand, 1890: “Appreciations” in 1889. 4th Thousand, 1890.

(Document courtesy of the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection at the University of Delaware)

Transcribed by Nicholas Santiago

ARTICLE II: ANALYSIS

Pater’s handwriting did not adhere to conventional styles of Victorian penmanship and writing. His technique instead was to never cross his letter T or define his letter N with the I’s dotted across the consecutive letter instead, making transcription a stimulating venture. This same biography was adapted closely to Pater’s entry in the online Wikipedia encyclopedia, as it states from his early work to his Renaissance work:

“The opportunities for wider study and teaching at Oxford, combined with formative visits to the Continent – in 1865 he visited Florence, Pisa and Ravenna – meant that Pater’s preoccupations now multiplied. He became acutely interested in art and literature, and started to write articles and criticism. First to be printed was an essay on the metaphysics of Coleridge, ‘Coleridge’s Writings’ contributed anonymously in 1866 to the Westminster Review.” -Pater’s Wikipedia entry.

Also notable is his opening line:

W.P. was born in London, on Sunday, Aug. 4, The Feast of S. Dominic,

August 4th is currently not the Feast of St. Dominic today; that day is on the 8th of August post-1970’s. Historically, the 4th is correct due to General Roman Calendars marking the day as so prior to 1970. A curious find is in the inclusion of St. Dominic at all given Pater’s connection to Christianity: St. Dominic, the Castilian priest and patron saint of astronomers, is beheld in predominantly Protestant sects, derivative of Christian history.

The original text ensures a reader be aware of his first publisher, being Macmillan, now one of the largest publishing enterprises. Accounts from scholars personable with his acquaintance identify him as prideful, namely regarding his history studying Classics and Philosophy, being a gifted student who read literature and philosophy beyond his years and often took decades of study to master and teach, accordingly. He took office at Brasenose via classical fellowship to teach German philosophy due in large part to his proficiency in the subject.

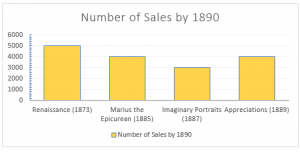

He notes a few times, “thousands,” and this is the amount of copies each book has sold. Each number is likely rounded and an exact number could not be made at the time.

As follows:

According to Mark Lasner, Pater’s collective works outsold Oscar Wilde in their respective lifetimes despite the decline in sales of Pater’s work; Wilde sold roughly 2000-3000 per book in a decade. His teetering and inquisitive belief in Christianity potentially hurt his sales, but as “Appreciations” debuted, which praised Wordsworth, Coleridge and appraised Dante Gabriel Rosetti, a powerhouse behind the Pre-Raphaelite Movement (which Pater well-respected and adapted his early works on), his works were looked at in favor once he purposely omitted his anti-Christian beliefs, which had previously earned his Renaissance book a blistering backlash and critique.

Following publication of his Plato and Platonism book, Benjamin Jowett had also praised his newfound style of criticism as Pater noted his rising cautiousness of establishment criticism, which would bring a larger pool of Aesthetic critics on board for or against his works.

A more intimate analysis of Pater’s biography speaks to his demeanor on the art of critique. His above biography, dotted with his accolades highlight his proficiency and credentials as a scholar, noticeably there is neither modesty nor humility in his words. There is merit in his pride given the prestige of an academic background being rare in the Victorian era.

at The King’s School Canterbury; he entered the University of Oxford, at Queen’s College, in 1858; took B.A. degree (2nd class in Classics) in 1862; was elected to an open Fellowship at Brasenose, in which college he has since held various offices, and took the degree of M.A. in 1865

He identifies not as an essayist or author nor one with normative interests, but as a top-performing scholar of philosophy and literature who holds multitudes of offices, at prestigious positions in Oxford. His travels to Italy, France and Germany, lands replete with then-untranslated knowledge that commoners could not visit with stricter and more broad socioeconomic hardships, was outlined in his biography to indicate the inherited experiences and knowledge he gained from interacting with – or at last observing – the many cultures abroad.

His excerpted biography also was written speedily and without much concern on readability, as to say there was no need to write a new and updated biography; future publications would only be worth holding a dated one. The excerpt, pulled from an already existing artifact was copied and resubmitted with the content nearly identical, to which the unknown publisher could have acquired this original text. Identifying himself in third person, but as “W.P” over “Walter Pater” shows sloppiness in formalities and implies that readers are supposed to be aware of his name without completely stating so, yet can denote some manner of confidence in ability, or that the work was not intended for the general public at first.

Pater painstakingly details his publications by precise year and sales number to show the frequency of his writings and the short time span between publications. Furthermore, as one man behind Aestheticism, he held undisclosed standards for critiquing that, based on one’s education verifies their ability to properly critique literature and art. Most authors and artisans had received some level of higher education which led them to drop out and create their own works that academia did not support. Pater believing that his way of remaining in university and acquiring astute understandings of Western philosophies allowed him to use German and Greek philosophy to objectively evaluate things on how one feels on first approach to a piece, far beyond physical beauty of the object they are observing.

This raises a question regarding the connection between the critic as the artist, and aestheticism through education: does one require a university education and be published on an academic matter to properly critique? To Pater, this appears so, considering that he could afford university and abroad trips that held knowledge a commoner could not find on the streets. The idea that one is unqualified to speak their opinion on a matter, or the belief that one need qualifications at all to express a sentiment or posit a theory is trademark upper-class normative behavior that removes more outlandish or misinformed information from entering academic discourse. Pater was an elitist on his area; only handfuls of people could truly afford an education and resorted to hearsay by degree-holding scholars. The critiques of the uneducated would not be held in the same respect as one who holds a degree and written books displaying specialty in the art of criticism.

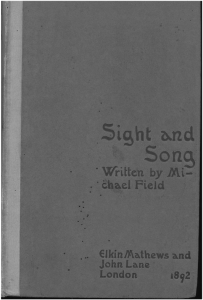

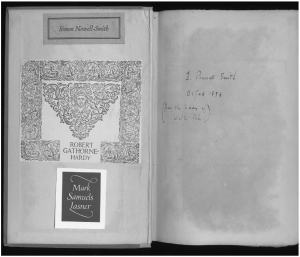

EDIT: Walter Pater’s copy of Michael Field’s Sight and Song (below) of 1892 can also be found at the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection. Field had been an avid reader and spiritual student of Pater’s and sent him a private copy to keep in his libraries. It was curated by Lasner in March 2014 after acquiring it for an undisclosed sum.